Presenting BlackSheep, one of today's fastest web frameworks for Python

According to recent runs of TechEmpower benchmarks, BlackSheep is one of today’s fastest web frameworks for Python [1.] [2.] [3.]. It is high time I write something about this project of mine!

When I acknowledge the good results shown in benchmarks, I don’t do it to boast. On the contrary, I think my actual contribution is so little, that Bernard of Chartres comes often to my mind: I feel like a dwarf on the shoulders of giants.

The contributions in GitHub demonstrate it: 1 direct contributor, 21.253 contributors in the dependency graph.

Even ignoring the amount of time spent by each person in the graph, and counting only the number of contributors, it turns out I contributed to my framework for its 0.0047%. If we were speaking about chemical purity of an object, I would be present only in traces.

In this post I describe the context of this web framework, discussing other solutions with similar background, and my favorite features in BlackSheep.

Context: BlackSheep uses asyncio

BlackSheep uses asyncio, the built-in infrastructure for event loops included in recent versions of Python. Event loops are used to support concurrent code and non-blocking I/O operations. For those who need context about this last sentence, I recommend to watch Ryan Dahl’s original presentation of Node.js, in YouTube.

from datetime import datetime

from blacksheep.server import Application

from blacksheep.server.responses import text

app = Application()

@app.route('/')

async def home(request):

return text(f'Hello, World! {datetime.utcnow().isoformat()}')

app.start()

Creative ferment around Yury Selivanov’s work

BlackSheep belongs to a group of frameworks inspired by Yury Selivanov’s work, and article uvloop: Blazing fast Python networking from 2016.

In extreme synthesis, Selivanov:

- Created a wrapper of libuv C library, to use it instead of the built-in implementation of event-loop in asyncio; he called it uvloop

- Created a wrapper of http-parser C library for Python, which he called httptools

- Prepared micro-benchmarks to understand the performance benefits of this approach

Both http-parser and libuv were originally designed for Node.js runtime. For both wrappers, Selivanov used Cython.

Side note: libuv was also adopted by Microsoft engineers for the new ASP.NET Core web framework and Kestrel HTTP server, and was used as default transport for Kestrel until its version 2.1. I think engineers at Microsoft were inspired by Ryan Dahl and Node.js, like Yury Selivanov - this topic would deserve a dedicated blog post.

ASGI or not ASGI

These frameworks can also be grouped by those that implement, or not implement, ASGI (Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface) specification.

Quoting its documentation:

ASGI (Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface) is a spiritual successor to WSGI, intended to provide a standard interface between async-capable Python web servers, frameworks, and applications.

The concrete benefit offered by ASGI is that web frameworks can use a shared infrastructure and switch between different implementations of servers. One of the greatest pluses of this approach, is the separation of concern of these components: ASGI servers can be concerned with lower level operations like handling connections, raw bytes of HTTP requests and responses, while web frameworks can be concerned with higher level operations such as routing, middlewares, etc. For example, Starlette is used on top of an ASGI server, which can be one of uvicorn, Hypercorn, or daphne.

| Server | ASGI | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sanic | - | The first framework using uvloop and httptools, “written to go fast”; its development started in 2016. Currently it implements both web server and framework; its contributors expressed the intention to adopt ASGI model. |

| uvicorn | ✓ | Core HTTP server developed by the same author of Starlette, concerned with low level operations and featuring a minimal design, valid base for higher level frameworks |

| Starlette | ✓ | Middle to high level API, can be used with any ASGI server; designed to be used as web framework or toolkit for higher level web frameworks |

| Vibora | - | Its goal is to be “the fastest Python http client/server framework”, according to micro-benchmarks prepared by its author, it is the fastest framework for Python |

| BlackSheep | - | Strongly inspired by ASP.NET Core and Flask, features dependency injection, model binding; aims at being feature complete and having clean source code |

And also, built on top of Starlette, therefore even higher level, like penthouse apartments:

| Server | ASGI | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Responder | ✓ | Higher level API, inspired by Flask and Falcon |

| FastAPI | ✓ | Features automatic generation of OpenAPI Documentation, I think appealing for people from with .NET background who are fascinated by the development speed offered by Python |

| Bocadillo | ✓ | Higher level API, aiming at providing a pleasant developer’s experience |

In this post, I am interested in discussing the web frameworks from the first table, as they either:

- include low level operations such as handling connections, reading and writing bytes for HTTP requests and responses.

- were developed together with such components by the same authors

When speaking about asynchronous web frameworks and ASGI, it’s important to mention Hypercorn and Quart, although they have a different background:

| Server | ASGI | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hypercorn | ✓ | Initially a part of Quart; inspired by Gunicorn, is seems to be the most feature-complete ASGI server, already supporting HTTP 1, HTTP 2; valid base for higher level frameworks |

| Quart | ✓ | Intended to provide the easiest way to use asyncio functionality in a web context, especially with existing Flask apps |

Hypercorn and uvicorn are both low-level ASGI servers; the first is more feature-complete, the second offers the best performance.

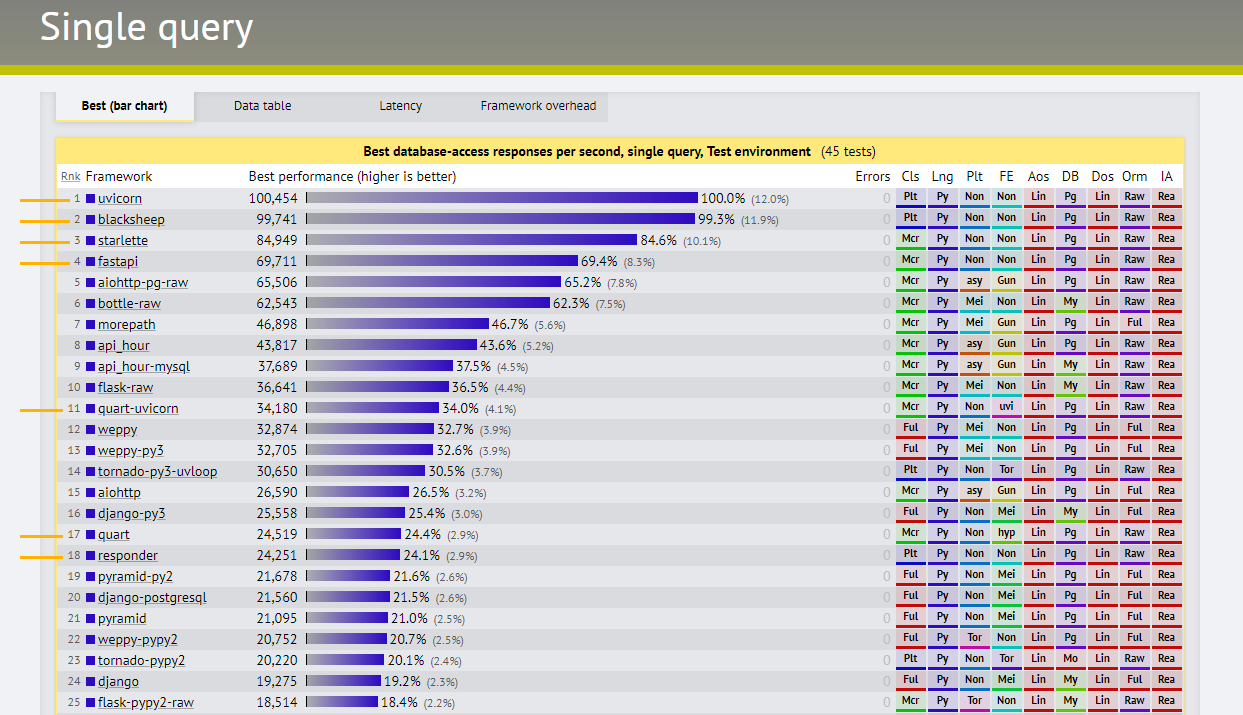

Some of the frameworks mentioned above are highlighted in the picture below, showing one of the recent results of TechEmpower benckmarks for the “Single Query” category (single database query). If we look at the “Multiple Queries” category, the difference between frameworks disappear: of course, since in this category they run 20 database queries!

Note how Responder, built on top of Starlette, eats most of the performance offered by the latter: this might be explained with the fact that Responder implements higher level abstractions to offer a more programmer-friendly API. Maybe these abstractions are not implemented in a way that avoids performance fees when they are not used. The same doesn’t happen in FastAPI, which is also built on top of Starlette. BlackSheep implements many abstractions, some of which are described below in this article and all described in the Wiki, and they are carefully designed to not cause performance fees when they are not used explicitly.

Why BlackSheep does not follow ASGI, and why it should

When writing the current version of BlackSheep, I decided to not follow ASGI for pretty much subjective opinions:

1. Curiosity

ASGI specification uses generic types to a large degree: dictionaries, tuples, and lists; to describe requests, headers, responses, parts of request/response cycle. For example, at each web request a scope like the following is created (copied from uvicorn documentation):

{

'type': 'http.request',

'scheme': 'http',

'root_path': '',

'server': ('127.0.0.1', 8000),

'http_version': '1.1',

'method': 'GET',

'path': '/',

'headers': [

[b'host', b'127.0.0.1:8000'],

[b'user-agent', b'curl/7.51.0'],

[b'accept', b'*/*']

]

}

The main reason why I didn’t adhere to ASGI, is that I was curious to investigate the performance benefits of custom extension types from Cython, using exact static typing. Python dictionaries and tuples cannot fully benefit from Cython static typing, because they are dynamic objects by design and there is no way to constraint the types of their keys and values.

Now, looking at the performance results in TechEmpower, it’s clear I didn’t manage to obtain a performance benefit over uvicorn and Starlette: the performance of these frameworks is pretty much equivalent [1.] [2.] [3.].

I still think I achieved good results with BlackSheep, but using custom extension types from Cython doesn’t come for free:

- working with Cython is harder and less portable than working in plain Python

- only a subset of Python developers wants to work with Cython

- every operation must be reimplemented, instead of adopting existing infrastructure (to support HTTP 2, for example)

- Python IDEs don’t usually provide hinting while writing code from Cython extensions

Vibora uses Cython too, and according to his author’s micro-benchmarks, it is much faster than any other Python web framework. Unfortunately this was not measured in the latest TechEmpower benchmarks, because tests were run in debug mode for Vibora. However, by admission of the same author in code comments, Vibora’s source code sacrifices cleanliness for the sake of performance:

#######################################################

# This is a very sensitive file.

# The whole framework performance is highly impacted by the implementations here.

# There are a lot of "bad practices" here, super calls avoided, duplicated code, early bindings everywhere.

# Tests should help us stay calm and maintain this.

# Raw ** performance ** is our ** main goal ** here.

#######################################################

This is not something I wanted for BlackSheep. If performance becomes that important for a web application, then I would stick to a programming language and web framework I know well: C# and ASP.NET Core, which eats any Python web framework by the long side performance-wise; and comes quite close in terms of development speed.

2. Use of generic classes to describe high level objects

The second most important reason why I wasn’t attracted by ASGI, is that I find unattractive its use of generic classes to describe high level objects such as HTTP requests, responses, headers.

This is of course, cultural bias on my side. I would prefer if ASGI defined interfaces, instead of concrete conventions based on dictionaries, lists, tuples. I am not alone: in Twitter I read a comment from Andrew Svetlov (author of aiohttp, the most mature framework for asyncio), in which he also criticized ASGI for its use of dictionaries - I don’t recall the exact words, though.

My .NET mindset is influencing me: I think nobody in .NET community would create a web framework that uses dynamic, or Dictionary<object, object> to describe web requests; and Tuple<byte[], byte[]> to describe HTTP headers.

But still, this is indeed cultural bias: both point of views are legit and make sense. Using generic types helps in keeping the specification low level and saving time in discussions such as: What kind of methods should a collection of HTTP headers (Headers) expose?.

3. Semantic taste

In ASGI, the “application” object is instantiated at every web request. I don’t like this use of the word: when I think about the “Application”, I think about something persistent in memory and in relation 1:1 with the running process. In ASGI, if you have 10 web requests, you have 10 instances of the “application”. The more I think about this, the more I dislike it, and I cannot help thinking this is exotic naming. When I speak about several instances of an application, I think about several processes in different geographical regions to achieve HA.

I wonder why, when MVC architecture is so popular, ASGI doesn’t call “Controller” the class that gets instantiated at every web request. Maybe because it is related to Django, which features a so called Model View Template (MTV) architecture?

However, not adhering to ASGI because of naming considerations, feels like throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

As you can judge from my words, I changed mind about ASGI and I am planning to work on a refactoring of BlackSheep to adhere to ASGI, finally following a recommendation that Tom Christie (uvicorn’s and Starlette’s author) gave me at the end of February; and Phil Jones (Hypercorn’s and Quart’s author) encouraged in April. Not only because of the perfomance matter explained above, also because the best features I implemented in BlackSheep are written in pure Python and are concerned with high level operations (more on this later). I see a great value in the separation of concern between the low-level HTTP server and the web framework component.

About Sanic

Unfortunately, I don’t know much about Sanic design, even though it’s on the field since three years. The feeling that contributors were “bullying” aiohttp at the beginning, didn’t make me feel favorable towards this framework. An acidic blog post written by Andrew Svetlov in 2018: “Sanic: python web server that’s written to die fast” (2018), makes me think my initial feeling was not wrong.

When I first read about this web framework, I had the feeling it was presented as “faster and better alternative to aiohttp”, and never felt this as a good-enough argument to use Sanic instead of aiohttp. However, I also think that the communication of Sanic’s contributors changed over years and today it looks respectful and reasonable.

As a side note, you can see the difference in the constructive way Yury Selivanov pointed out some performance issues in aiohttp, in his aforementioned article. If you look for aiohttp-pg-raw in recent TechEmpower results linked above, you can see that aiohttp performance is not bad at all today. Since Python is already hit by a good deal of crappy criticism from some other communities, even at the peak of its popularity✱, it’s best if members of its community keep positive towards each other.

✱ The last resort of judgy people who like to criticize, when faced with vast popularity of the thing they enjoy to criticize, is to use elitarian idiocy:

- “It’s popular because it’s simple and new programmers are unable to use more complex languages”

- “It’s popular because it’s vulgar / stupid”

The same dynamics can be seen in many fields: music, cinema, arts, politics.

About Vibora

When Vibora was announced in Twitter, with micro-benchmarks and its captivating website (a bit boasting, calling it a “sexy framework”), it obtained a lot of visibility and about 4K starts in GitHub in a few days.

I exchanged a couple of emails and messages in GitHub with Frank Vieira, Vibora’s author, and I think he is a very nice person, kind and helpful. Vieira is working on a complete rework of Vibora and he started again from scratch, as he explained in GitHub and in interviews.

Vibora is extremely interesting because of the performance it promises, but as it stands currently, I see two defects in it:

- it is not truly open source: it’s being developed privately and published open source; like enterprises do with some of their projects - smells of “waterfall OS”

- the idea of sacrificing code cleanliness for the sake of performance, it won’t pay off in the long run

I am looking forward to seeing the next version from Vieira.

About uvicorn and Starlette

Aside from aiohttp, which is mature, and considering only the emerging asynchronous frameworks for Python, I think the most interesting ones are those by Philip Jones: Quart and Hypercorn; and those by Tom Christie: uvicorn and Starlette.

I admire Tom Christie, I think he is one of the most valuable professionals contributing to Python community. He communicates in a brilliant, elegant, and positive way, never boasting - even though boasting proves to help with popularity and visibility. My opinion is based on a few emails and messages I shared with him, and many of his tweets, and the documentation he wrote for his projects.

As written previously, Starlette is designed to be used as web framework, or toolkit for higher level web frameworks. From my point of view, Starlette is already high level and it is best to contribute with libraries that integrate with it, rather than inventing new web frameworks on top of it. I see a limitation of the second approach: for example if FastAPI is used to benefit from its automatic generation of OpenAPI documentation, most likely other web frameworks like Responder and Bocadillo are not used together, to benefit from their abstractions: each of these implement its own API to start the web application, and use a new name.

To introduce the last topics, I mention one thing I disagree with Tom Christie about. Once I read a tweet in which Tom Christie called dependency injection pattern “fluff”, or something like that. I couldn’t disagree more about this: I think dependency injection improves the architecture, simplifies testing, and reduces the amount of code that must be typed, also in Python. This pattern is generally not popular in Python community, as many programmers think it is

- not necessary, as you can attach references to object dynamically

- un-pythonic, it looks “enterprisey”

The result of attaching references and reading them where they are needed, is cumbersome and ugly in practice - I can provide examples if challenged, now I don’t want to make this post even more verbose than it already is.

The second common argument puzzles me, because I think DI is one of the most “Pythonic looking” design patterns, and moreover PEP 484 creates many interesting opportunities on this front.

My favorite features in BlackSheep

The favorite features I implemented in my framework, are:

- built-in support for dependency injection

- automatic binding of request handlers’ input parameters

- normalization of request handlers and middlewares

Dependency injection

BlackSheep supports built-in dependency injection for request handlers and middlewares. The Application object exposes a services property, which can be used to activate services.

When a request handler defines a parameter whose name, or type annotation, is configured in the services object, this service is automatically injected to the function call of the request handler.

Dependency injection is provided by rodi, a library I wrote, supporting singleton, scoped, and transient life style for activated services. Singleton services never change after first activation, scoped services are activated once per resolution context (potentially once per web request), and transient services are activated every time they are required.

Consider an example of common scenario:

- a web application that serves data about cats

- PostgreSQL is used as persistence layer for all cats data

- when running tests, it is desired to use mocked data access classes, with in-memory implementations, the business logic doesn’t reference directly the PostgreSQL implementation

The application can define an abstract class CatRepository, an implementation for automated tests InMemoryCatRepository, and a real one for the application PostgresCatRepository.

Services are first registered when configuring the application at startup, using a Container:

from rodi import Container

container = Container()

When configuring the application for your automated tests, you want to register a service using the mock cat repository:

container.add_singleton(CatRepository, InMemoryCatRepository)

When configuring the application for your real run, you want to register the repository that uses Postgres:

container.add_singleton(CatRepository, PostgresCatRepository)

Note that services are instantiated receiving injected parameters to satisfy their constructor. For example, if the PostgresCatRepository needs db settings, its constructor can look like:

class PostgresCatRepository(CatRepository):

def __init__(self, db_settings: DbSettings):

self.db_settings = db_settings

And this second service must be registered, too:

container.add_singleton(DbSettings(

connection_string="...example..."

))

When defining request handlers, services are automatically injected by the framework, if function arguments are registered in app.services:

@app.route('/:cat_id')

async def get_cat(cat_id: str, repo: CatRepository):

return await repo.get_cat(cat_id)

The Services from rodi also supports a simplified notation, that doesn’t require configuring a Container, but using this simplified notation only supports singletons:

from blacksheep.server import Application

app = Application()

# app.services is an instance of rodi.Services, and it lets register new singletons to it

# this is to offer a simpler API, but it's limited as it doesn't support resolution

app.services[CatRepository] = PostgresCatRepository(DbSetting({

connection_string: '...example...'

}))

To those who think DI is not needed in Python, I recommend to give it a try, I am confident that many will change their mind when they see it in practice.

For more information on rodi, please see its project in GitHub.

Model binding

BlackSheep implements “Model Binding”, another feature inspired by ASP.NET web framework, consisting in automatic binding and parsing of request parameters. This improves code quality and developer’s experience, since it provides a strategy to read values from request objects, and removes the need to write inside request handlers parts that read values from query string, body, headers, etc.

Request handlers are normalized at application startup, and depending on their signatures, binder classes that extract parameters from requests are configured. Binding can be implicit, or explicit when the programmer specifies exact binders from blacksheep.server.bindings.

I also use the terms “Value Binding” and “value binders” to describe this feature.

Value binders can be defined explicitly, using type hints and classes from blacksheep.server.bindings, and represent a creative use of the type hinting feature in Python:

from blacksheep.server.bindings import (FromJson,

FromHeader,

FromQuery,

FromRoute,

FromServices)

@app.router.put(b'/:d')

async def example(a: FromQuery(List[str]),

b: FromServices(Dog),

c: FromJson(Cat),

d: FromRoute(),

e: FromHeader(name='X-Example')):

pass

In this case, the request handler for HTTP PUT on /:d/ route, will get called after extracting parameters from the request object:

- a list of strings from the query string, from a parameter with name ‘a’

- a service of type

Dog, from configuredapplication.services(Dependency Injection) - a request body JSON payload, of type

Cat - a string, from

droute value - a string, from

X-Examplerequest header

If input parameters cannot be extracted, a BadRequest exception is raised and the client receives HTTP 400 explaining the cause of the problem.

Implicit binding

Binding happens implicitly when:

- a request handler has a signature with parameters different than

request - parameters are not annotated with types, or are annotated with type hints that are not instances of

Binderclass

An example of implicit binding is as follows: in the request handler below, culture_code and area are read from request route values, because the route contains parameters with matching name.

@app.router.get(b'/:culture_code/:area')

async def home(request, culture_code, area):

return text(f'Request for: {culture_code} {area}')

In this case, configured binders are of type FromRoute.

Implicit bindings happen with this priority:

- If the route contains a parameter with matching name, a

FromRoutebinder is configured. - If a service is configured inside app.services, matching by name or type hint, a

FromServicesis configured. - If the parameter type hint is not configured, or is configured as a type that suits query string parameters (

str, int, float, bool, List, List/Sequence/Tuple[str/int/float/bool]) then aFromQueryparameter is configured. By default a list of strings is injected when the request handler is called. - If the parameter has a type hint different than simple types listed above, then a

FromJsonbinder is configured.

Explicit and implicit binding can be mixed freely, so this is a valid example:

@app.router.post(b'/:culture_code')

async def example(request, culture_code, item: FromJson(Item)):

# culture_code comes from route (is a str)

# item is an instance of Item class, parsed from JSON input

return text(f'Request for: {culture_code}')

It is possible to define custom binders, subclassing from Binder, SyncBinder, and other classes from bindings module. Since these are abtract classes, it’s easy to know what methods must be implemented to make them work.

To define optional parameters, there are two options:

- using

typing.Optional - specifying

required=Falsewhen configuring explicit binders

@app.router.get(b'/')

async def example(a: FromQuery(List[str] required=False):

pass

Normalization of request handlers and middlewares

Function normalization in BlackSheep refers to the set of features that facilitate the definition of request handlers and middlewares, to offer a better experience to programmers and enable faster development.

I am very satisfied with the solution I came up with, when it comes to defining middlewares and request handlers: it uses the “function as first class citizens” to the maximum, with wrapping, reflection code from inspections carefully ran once.

Tests I executed with wrk show that the performance price of this approach is little and acceptable.

A normal request handler is defined as an async function, having as input a blacksheep.Request object and returning an instance of blacksheep.Response.

@app.route('/home')

async def home(request: Request) -> Response:

pass

However, request handlers can be defined with different signatures, depending on their expected parameters, and they are normalized at application startup. Parameters defined in request handlers are injected automatically, like described previously for Model Binding.

Middlewares support the same kind of normalization, and dependency injection, so these are all valid middlewares in BlackSheep:

async def middleware_one(request, next_handler):

return await next_handler(request)

async def middleware_two():

pass

async def middleware_three(cats_repository: CatRepository):

pass

async def middleware_four(request, next_handler, authorization: FromHeader()):

# authorization parameter is injected with a str read from 'Authorization' requets header

pass

Conclusions

As usual, there is a lot of creative ferment around web frameworks, and particularly so in Python community. I hope readers will find this article interesting and decide to try some of these frameworks.

In the free time, I will try to contribute to Python community working on frameworks and writing common libraries to handle things like OpenID Connect flows and OAuth standard in the context of asynchronous applications.

The BlackSheep logo was drawn using my Lamy fountain pens.

🐑